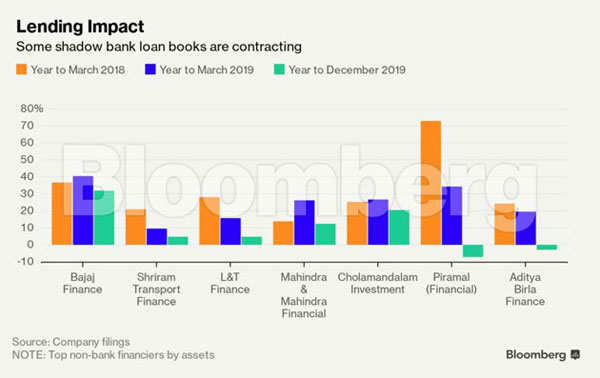

In the second week of April, deep into India’s initial 21-day lockdown to curtail the spread of the coronavirus, senior officials at Bajaj Finance Ltd. held a conference call. The prognosis wasn’t good.

In just 10 days the keystone shadow lender had lost 350,000 customers and almost $651 million in assets under management. Small and medium enterprises were under strain and it was considering setting aside money for losses in case large borrowers went under.

“We are in an uncharted zone,” Rajeev Jain, managing director of the Pune-based company, said on the call.

For India’s financial sector, the coronavirus freeze is just the latest headwind in a multi-year storm that’s dragged down consumption and seen the nation lose its crown as the world’s fastest-growing major economy. Now, if bad loans rise as many including the central bank expect, banks and shadow lenders are set to become ever more cautious just when credit is most needed to keep the economy going.

Bloomberg

“This is a stall of the economy that has never been experimented before,” Jain said. To try to get through the next few months, Bajaj Finance will avoid lending to self-employed borrowers and cut loans to small and medium-sized businesses.

The pandemic has hit India’s economy just as green shoots were emerging. The International Monetary Fund has slashed its growth projection for India to 1.9% for the financial year 2021 from 5.8% estimated in January. Even that looks optimistic compared to what private economists are forecasting, with some having penciled in the first contraction since 1980 this year.

India’s $1.7 trillion banking system plays an out-sized role in the country. The industry’s struggles in recent years have been one of the main reasons for a slowdown in the $2.7 trillion economy, Asia’s third-largest.

Bloomberg

“India’s financial system has had a rocky few years,” said Pranjul Bhandari, chief India economist at HSBC Securities and Capital Markets Pvt Ltd. in Mumbai. “The recognition and provisioning for high loads of bad debt at banks took a toll over 2015-2018, ending with a fallout at the shadow banks.”

The seeds of stress were sown even earlier, in a debt-fueled economic boom between 2007 and 2012 when banks increased loans by 400%. When the economy began slowing, many companies struggled to repay debts, making banks reluctant to lend as bad loans piled up.

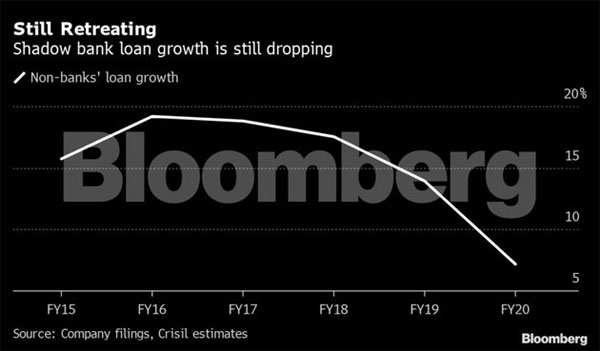

Some of the slack was then picked up by shadow banks — lenders that don’t rely on deposits and are typically less regulated. But a default by one of the most prominent of those — Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Ltd. — in 2018 saw that lending dry up too.

Bloomberg

The collapse triggered a credit crunch, forcing the Reserve Bank of India to step in to take control of another shadow lender, Dewan Housing Finance Corp., to contain the fallout. A smaller lender also failed in 2019 after allegedly duping investors about its exposure to a property developer.

Then, in March this year, the central bank seized private-sector Yes Bank Ltd. in India’s biggest bank rescue. Alka Anbarasu, senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors’ Service in Singapore, said the ripple effects of the Yes Bank rescue will hurt smaller private sector banks and further complicate the situation for shadow lenders that are already battling tight funding conditions.

“Companies relying on either type of lender for funding, many of which have weak financials, will have difficulty in maintaining liquidity, which can result in defaults on loans from banks and shadow banks,” she said. “As loan losses at shadow banks increase and threaten their solvency, banks’ direct exposures to them can be at risk.”

Desperate to avoid such a chain of events, the RBI has injected $6.5 billion into banks to promote lending to shadow banks and small borrowers, further relaxed bad-loan rules and barred lenders from paying dividends in the current fiscal year through March 31 so that they can preserve capital.

“The overarching objective is to keep the financial system and financial markets sound, liquid and smoothly functioning so that finance keeps flowing to all stakeholders, especially those that are disadvantaged and vulnerable,” Governor Shaktikanta Das said in an address on April 17.

On the stock market, sentiment has dropped like a stone. The S&P BSE bank index has plunged about 40% this year versus a 26% decline for the benchmark index.

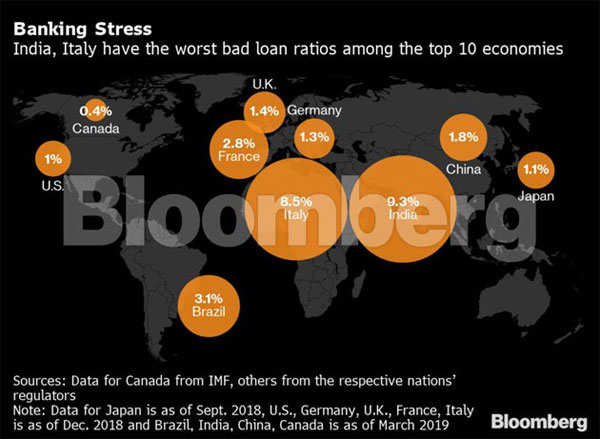

The central bank in 2015 under then-Governor Raghuram Rajan began tackling the bad loans in earnest, bringing to light the full scope of the problem. Gross non-performing assets surged from about 3% to more than 9%, then breached 10% for the highest ratio in the world.

The government created a new bankruptcy law to aid loan-recoveries but, as the economy slowed, authorities started to show more leniency toward certain borrowers and small businesses. The Reserve Bank warned in December of a pickup in bad loans again, with soured debt forecast at 9.9% of total credit by September 2020, up from 9% predicted earlier.

Urjit Patel, who succeeded Rajan as central bank governor and imposed stringent curbs on weak lenders to get them back into shape, says more bad news is in store for the industry.

“The forbearances pre-Covid, together with widely reported delays in resolution and the ad-hoc dilutions in regulations, have not helped; neither has poor disclosure,” Patel wrote in a recent opinion piece in a local newspaper.

The bad loan mess is getting in the way of monetary policy too, as banks hold back from passing on the bulk of the 210 basis points of interest rate cuts that the central bank undertook from February last year. They have also been shy to lend and as a result, overall loan growth has slowed to its lowest level in more than two years.

That’s one of the reasons the RBI is trying to channel cash to hard-up businesses with measures such as a 500 billion-rupee targeted injection to support companies and lenders, announced on April 17.

Bloomberg India economist Abhishek Gupta expects policy makers to do more, including introducing a government-backed credit guarantee scheme. But even that might have limitations given the fragile state of the financial sector.

“Our projected recession for the real economy ahead should exert an even greater pressure on the banking system due to a likely rise in the non-performing assets,” he said. “That is likely to further lower the risk tolerance levels of banks, push up the risk premium for lending to smaller and weaker-rated firms and further weaken the credit intermediation process.”